- The Russian Orthodox Old-Believer Church, which preserves apostolic continuity and purity of the Orthodox faith

- Nikon’s reforms — the beginning of schism

- Old-believers in the 18th and 19th centuries

- The spiritual centers of old-believers

- Divisions among old-believers

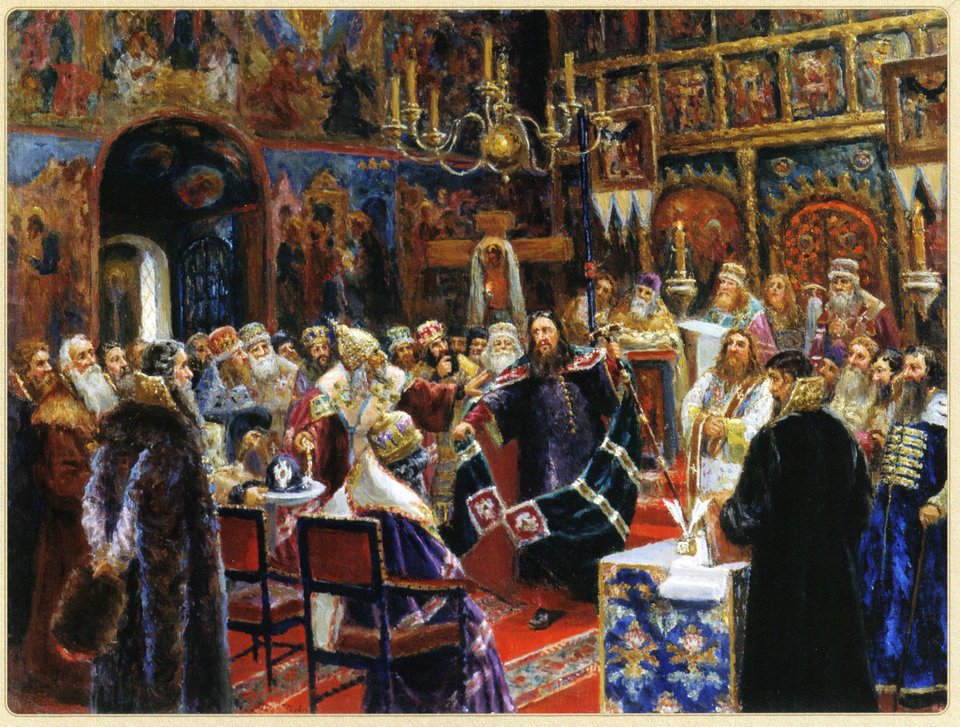

Having deposed Nikon, this council elected a new patriarch, Ioasaph, the ex-archimandrite of the Trinity-St. Sergiy Laura. They, then, addressed the issues caused by church reform. This reform was convenient to many. The eastern patriarchs supported it, as it was based on the recently published Greek books, which fixed their supremacy in matters of faith, asserting their spiritual authority (hitherto faded in Russia). Secular authorities also saw their geopolitical interests advanced by the reform. Even the Vatican had an interest in reforming the Orthodox Church. With the annexation of the Ukraine to Moscow, Russia began feel a greater influence from the west. Numerous Ukrainian and Greek monks, teachers, politicians and various merchants came to Moscow. All of them were, to a degree, imbued with Catholicism.

The Councils of 1666-67 approved the recently published books and the new rites and imposed terrible anathemas on the old ones, including the two-finger Sign of the Cross. They cursed those who, in the Creed, confess the Holy Spirit as “True” and life-giving God. They cursed those who serve using the old books. In conclusion, the councils pronounced, that, “if one does not submit… he is to be excommunicated, cursed and anathematized as a heretic and a defiant, to be cut off like a rotten member. If one remain disobedient to the death, he (or she) will be doomed in the afterlife, and his soul shall be with Judas the traitor, Arius the heretic and the other damned heretics. Iron and stone will sooner decompose than he see pardon, for never shall it be granted, never in all eternity. Amen.”

These terrible oaths angered even Nikon, who was accustomed to damning Orthodox Christians. He said that they were lain on the entire Orthodox host, and recognized them as reckless.

In order to compel pious Russians to accept this new faith, the council threatened to subject the disobedient to “bodily animosities,” that is, to the excoriation of bodily members. Likewise, they were whipped with beef tendons, exiled and imprisoned; this brought about even greater unrest and aggravated the schism. Tens of thousands were burned in cottages, or otherwise pacified.

The modern new-rite church, in a local council of 1971, recognized the mistakes made by Patriarch Nikon and the Councils of 1666-67 that led to the tragic division of Russia’s Church. It admitted that the old rites are “equal and saving” and proclaimed the oaths ill-advised and “unreasonable.” As a result, the reforms were reckoned “canonically and historically unfounded.” But, unfortunately, the recognition of these mistakes had changed little in the attitude of the Russian Orthodox Church to the old books and rites, or to the old-believer Church.

A schism did not take place immediately. The decrees of the council were so overwhelming and mad that Russians considered them diabolical. Many thought that the tsar was temporarily deceived by the visiting Greeks and Catholics and that, sooner or later, this deception will be revealed and everything will return to normal. As for the bishops who participated in the council, people considered them weak-willed and easily manipulated. One of them, archimandrite (later, patriarch) Ioachim, openly declared, “I know neither an old faith nor a new one, but what the bosses bid, the same I shall execute and be obedient to them in everything.”

For 15 years after the council, there was wrangling between the supporters of the old faith and the followers of the new one, between representatives of the ancient, people's church and those of the new, tsarist one. Archpriest Avvakum promulgated one message after another to Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, calling him to repentance and persuading him to remain in the ancient Orthodoxy so ungraciously cursed by the council.

The Tsar was advised to organize a national debate, but (naturally) refused. Yet debates were set up, with the outcome of the opposing side getting exterminated for turning up and opening their mouths. After the tsar’s death, the reins of the domain were taken by his son, Theodore Alexeevich. The defenders and confessors of the ancient Church turned to the new tsar with a warm impetration “to return to the faith of the pious and holy forefathers,” but all petitions were unsuccessful (the petitioners, terminated).

Persecutions continued until 1905. The mass slaughter of the late 17th century was supplanted by Peter’s double taxation. (You might have heard about his beard tax, as it is mentioned in most western high-school textbooks.) But even if one registered as “a schismatic” (which registration was not popular, by the way, as such terminology is offensive) one was not immune from persecution. People’s kids were expropriated for indoctrination, regardless of registration. Exile awaited others. Books and icons were confiscated, but a worse fate awaited those who “spread schism.” Up until the Revolution of 1917, (like in many Muslim countries of today) if one facilitated the conversion of someone from the mainstream creed to old-rite Christianity (by giving him or her books, for example) one was liable to severe reprisals. Exile to Siberia was the usual punishment for such heinous felony. Meanwhile, officials from the ruling church (often styled, the treasury’s church) trod the land seeking converts, and woe to those who opposed their arguments with anything coherent — an investigation would have been inaugurated. The methods employed by these evangelizers differed from those of the 17th century, but both were reminiscent of those of the Diocletian era — if tender guile did not succeed, it quickly turned to wrath. Reprinting pre-schism books was also forbidden (except for a time under Catherine II), yet old-believers found a way to scribe and print the necessary folia — literacy among them was higher than that of the general population, as most children were taught to read by their parents. (Even today, old-believers from South America to Australia learn to read using the Horologium and Psalter.)

The article was translated, with omissions, from rpsc.ru

by Andrei Andreevich Shchegoliaev and Alexey Logvinenko for nashavera.com,

but this last paragraph was appended by an editor.

Discussion

(0)

Discussion

(0)

Congratulations! You have registered!

Congratulations! You have registered!